Peter Konsek knew there was no straight path out of a maze built by generations of power and entitlement. As he drove away from Felcsút, the shadow of the Pancho Arena lingering in his rearview mirror, he found himself returning to a thought that had gnawed at him for weeks. The problem wasn’t just the scale of wealth and influence wielded by figures like Lőrinc Mészáros—it was the structure supporting them, a system designed to perpetuate itself through unaccountable family ties and hypocritical leadership. And, in some ways, Peter saw his own struggles mirrored in theirs.

Mészáros, the “everyman oligarch,” had built his empire with undeniable cunning. But what fascinated Peter wasn’t the man’s rise; it was how quickly the foundation of his success began to mirror the very problems it claimed to solve. Holding companies like Opus Global ZRT were ostensibly set up to drive efficiency and economic progress. Instead, they became vehicles for distributing wealth and opportunity among a closed circle of loyalists—friends, family members, and associates—many of whom lacked the expertise needed to manage the empire’s sprawling operations.

Peter had seen the consequences firsthand. Workers in Felcsút whispered about mismanaged projects, where delays were blamed on everything from supply shortages to unforeseen weather, but were, in reality, the result of unqualified leadership. Contractors hired through personal connections made decisions that cost both time and money, while talented professionals watched from the sidelines, their expertise undervalued in a system that prized loyalty above all else.

What struck Peter most was the hypocrisy. Publicly, these oligarchs championed the idea of a strong and independent Hungary, free from foreign influence and driven by the strength of its people. Privately, their actions revealed a different story: a reliance on nepotism that stifled innovation and created a culture of entitlement. It wasn’t just Mészáros. The same patterns appeared in the ventures of István Tiborcz, Ákos Várna, and others. These men weren’t just building businesses—they were building dynasties. And in doing so, they were repeating the mistakes of the aristocracy they had replaced, treating their empires as family legacies rather than engines of progress.

Peter couldn’t help but see a parallel in his own life. His caravan business had started as a family endeavor, a way to bring people closer to nature and freedom. But as it grew, he had turned to his brother and cousins for help, believing that shared blood would translate into shared vision. It hadn’t. The business floundered under their management, with missed deadlines, botched deals, and a creeping sense of resentment that festered among them. Peter’s brother, tasked with logistics, had ignored supplier contracts in favor of handshake deals that fell apart under scrutiny. His cousin, managing finances, had siphoned profits into personal projects, confident that Peter wouldn’t challenge him.

The lesson had been painful but clear: family alone wasn’t enough. Responsibility required more than trust—it required accountability, professionalism, and a willingness to make difficult decisions. The very things Peter had struggled to implement in his small business were the same flaws writ large in the empires of Hungary’s oligarchs.

Take the case of Opus Global ZRT, a holding company that controlled vast assets across energy, tourism, and construction. On paper, it was a model of diversification and resilience. In practice, it was a labyrinth of overlapping interests, with key positions held by relatives and allies whose decisions often prioritized short-term gains over long-term stability. One project, a state-funded hotel chain, had collapsed under the weight of mismanagement, leaving behind debts that trickled down to subcontractors and workers who would never see their wages. Another venture into renewable energy faltered when underqualified executives failed to navigate the complexities of international markets.

Peter read about these failures and saw a familiar pattern: the same reliance on family and loyalty over expertise, the same resistance to outside talent, the same unwillingness to admit mistakes. It wasn’t that Mészáros himself was incompetent—his ability to navigate Hungary’s political and economic landscape proved otherwise. But the structures he had built mirrored his own assumptions about power, trust, and control. And those structures were failing the people they were meant to serve.

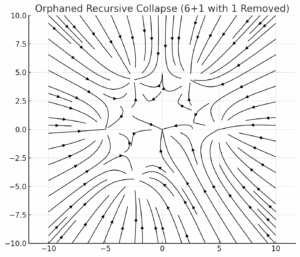

This dynamic wasn’t unique to Hungary. Peter had studied the oligarchies of Russia, where figures like Roman Abramovich had built vast fortunes by blending political connections with shrewd business strategies. But there was a difference. In Russia, the top-tier oligarchs often operated like CEOs, surrounding themselves with professionals whose expertise drove their ventures to success. In Hungary, however, the second and third layers of leadership—the lieutenants, managers, and directors—often acted as miniature oligarchs themselves, replicating the system’s flaws on a smaller scale. The result was a cascade of inefficiency, where even well-intentioned projects lost their way under layers of mismanagement.

The hypocrisy was impossible to ignore. Publicly, the oligarchs preached self-reliance and hard work, while privately they relied on the privileges of birth and connection. They presented themselves as stewards of Hungary’s future, yet their actions eroded the very foundations of trust and meritocracy that a stable society needed.

As Peter reflected on these dynamics, he realized that the problem wasn’t just structural—it was cultural. The oligarchs had built their empires on the assumption that family would always act in the best interest of the whole. But family, like any other group, was subject to the same flaws of ego, ambition, and self-interest. Without accountability, loyalty became a weakness rather than a strength.

Driving away from Felcsút, Peter thought about his own business. He had learned to make hard choices, replacing family members with outside talent who could bring the professionalism his company needed to survive. It hadn’t been easy—he still felt the sting of his brother’s words, accusing him of betrayal. But the results had been undeniable. The business was growing again, its reputation restored.

The same lessons, Peter thought, could apply to the oligarchs. Their empires weren’t doomed by their size or ambition; they were doomed by their unwillingness to adapt. A shift toward meritocracy wouldn’t just benefit their businesses—it would benefit the country. Workers would thrive under competent leadership, citizens would see the tangible results of investment, and Hungary could reclaim the sense of progress it so desperately needed.

As the rain began to clear, Peter saw the outlines of the Pancho Arena fading in the distance. He thought of the proverb his father used to say: “A család szent, de nem mindig bölcs.” Family is sacred, but not always wise.

Peter didn’t know how far his journey would take him, but he knew this: trust without accountability was no foundation at all. The mosaic wasn’t broken beyond repair, but it needed new hands to rebuild it—hands that understood that progress was never a gift; it was always earned.

Thank you for your rewarding attention,

Dr. Attila Nuray