Peter Konsek hadn’t planned to stay this long in Budapest, but the city had a way of pulling him deeper into its secrets. It was a place of contradictions—grand avenues built on fading foundations, public prosperity masking private despair. Beneath the surface of Hungary’s capital, Peter uncovered a mosaic of influence so intricately designed it almost felt like art. But the deeper he looked, the more he realized it wasn’t art—it was a puppet show.

He was drawn into this world by a name: Bence Tuskán. Tuskán wasn’t a household figure, nor did he seek the spotlight like some of Hungary’s more flamboyant oligarchs. Instead, he thrived in the shadows, orchestrating deals that shaped the nation’s economy. Peter’s first lead came from a retired journalist who frequented the same café. “If you want to understand Hungary’s game,” the man said, his breath curling in the cold air outside, “don’t follow the headlines. Follow the money. And start with Tuskán.”

Peter began tracing Tuskán’s network, which led him to NN, an ambiguous entity that seemed to surface in every major government grant. Ostensibly, NN was a holding company for state-private partnerships, tasked with overseeing development projects from infrastructure to tourism. In practice, it was a funnel—a conduit through which public funds flowed into private pockets. The National Bank of Hungary’s grant programs, ostensibly designed to support innovation and economic growth, had become NN’s primary source of funding.

One such project was a luxury development on Lake Balaton, nominally managed by Áron Varga, a businessman with ties to Tuskán. The project, Peter discovered, was funded through a €12 million government grant channeled via NN. Officially, the funds were earmarked for “regional tourism enhancement.” Unofficially, they disappeared into a web of shell companies, each more opaque than the last. By the time Peter tracked the money, it had resurfaced in offshore accounts, leaving only a half-finished hotel and unpaid subcontractors in its wake.

It wasn’t just about the money—it was about power. The grants weren’t distributed based on need or merit. They were tools, used to reward loyalty and punish dissent. Contractors who questioned delays or demanded transparency were quietly blacklisted. Their calls went unanswered, their bids rejected, their livelihoods crushed under the weight of bureaucracy.

As Peter dug deeper, he discovered another layer of the mosaic: the house mafia, a shadowy network that targeted vulnerable homeowners under the guise of legal processes. The connections between Tuskán’s empire and the house mafia were tenuous but undeniable. In one case, Peter uncovered a property acquisition tied to NN. The house, seized from an elderly couple under dubious psychiatric evaluations, had been transferred to a development firm linked to Tuskán. The firm’s owner, a close associate of NN’s leadership, had then used the property as collateral for further government-backed loans.

These weren’t isolated incidents. Peter found dozens of similar cases, each following the same pattern. Vulnerable individuals were declared unfit, their assets liquidated under the supervision of compliant courts and doctors. The profits flowed upward, disappearing into the opaque channels of NN and its affiliates. The National Bank, meant to safeguard Hungary’s financial stability, seemed complicit, its grants providing the veneer of legitimacy for what was essentially state-sanctioned plunder.

Peter’s investigation wasn’t without risk. His conversations were interrupted by long silences on the other end of the line. Documents disappeared from public records before he could access them. Once, as he left a meeting with a whistleblower, he noticed a car idling too long on the corner. The fear was palpable, and it wasn’t just his own. The people he spoke to—construction workers, doctors, even mid-level bureaucrats—whispered their stories like confessions, their eyes darting to unseen watchers.

It was in one of these whispered conversations that Peter learned about the Sovereignty Protection Office’s investigation into Transparency International Hungary and Átlátszó, two of the country’s most prominent anti-corruption organizations. Officially, the investigation was about “foreign influence.” In reality, it was an attempt to discredit their reports on public procurement corruption—reports that named Tuskán and NN among the chief beneficiaries.

Peter read through Transparency International’s findings, which painted a damning picture of inflated contracts, insider deals, and misappropriated funds. In one instance, a €3 million energy contract awarded to an NN affiliate had been subcontracted to a firm with no experience in the sector. The result was predictable: delays, cost overruns, and a final product that barely met safety standards.

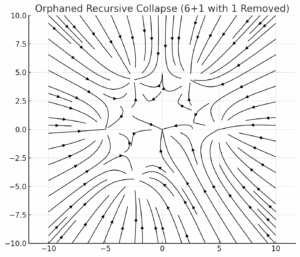

The parallels to a puppet show became impossible to ignore. On stage were the visible players—Tuskán’s proxies, NN’s executives, the media figures parroting state narratives. Behind the curtain were the puppet masters, figures like Tuskán himself and the Minister of Interior, who shaped the rules of the game. These men weren’t loud or ostentatious. They didn’t need to be. Their power lay in the strings they pulled and the fear they instilled.

Peter saw this fear in everyday interactions. A café owner he interviewed spoke cautiously about a recent construction project funded by NN. “They came in with promises,” the man said, “but we never saw the money. The workers were paid late, if at all. And when we asked questions… well, you learn not to ask questions.”

Fear wasn’t just a byproduct of the system—it was its foundation. The rigidity of behavior, the unwillingness to challenge authority, the quiet acceptance of “how things are done”—these were the strings that kept the mosaic intact.

Peter sat in his apartment that night, the glow of his laptop casting faint shadows on the walls. The mosaic had never been clearer. The grants, the house mafia, the centralized power of NN—it all fit together, a pattern of control designed to reward loyalty and crush dissent. And yet, for all its complexity, it was fragile. The puppet masters thrived on silence, on the belief that their strings were invisible. But Peter knew the truth: once the strings were visible, the whole show could come crashing down.

He thought of the proverb again: “Az Isten háta mögött.” Behind God’s back. It wasn’t just a place—it was a state of mind, a way of living that accepted the shadows as inevitable. But Peter wasn’t willing to live in the shadows anymore. He didn’t know how to cut the strings, but he knew the first step: make them visible.

Teaser for Next Episode: As Peter delves deeper, he finds that the shadow economy extends beyond businesses and property—it seeps into the media, shaping narratives and manipulating the public. Next: The Sport-Media Moguls and Their Masterpieces.

Thank you for your rewarding attention,

Dr. Attila Nuray