Peter Konsek sat at the edge of Budapest’s bustling Oktogon Square, staring into his coffee as memories of his television debut bubbled to the surface. It had been years since he participated in the national cooking competition—a moment that had promised a bright future. Yet the experience had left a sour taste. The grueling hours, the intense filming, and the emotional highs and lows had taken their toll. He hadn’t been paid, nor had he won the competition. Worse, his image had been splashed across the country for years, thanks to a clause in the contract that allowed the network to use his likeness indefinitely.

He hadn’t realized it then, but his experience was a microcosm of a much larger problem in Hungarian media. Behind the glamour of the screens, actors, presenters, and participants were treated as expendable commodities. Contracts heavily favored the networks, allowing them to extract maximum value from individuals while silencing or sidelining those who dared to challenge the system. And in Hungary’s tightly controlled media environment, dissent—especially on political or equity issues—came at a steep price.

Peter’s interest in the media grew after that experience, and he soon found himself investigating the institutions that shaped Hungary’s narrative landscape. At the center of this ecosystem was the Media Authority (Médiatanács), a regulatory body responsible for overseeing television, radio, and digital content. Ostensibly, its role was to ensure fairness and balance. In practice, Peter discovered, it often acted as a gatekeeper for government-approved narratives.

One case stood out to Peter. A popular television actor, Tamás, had used his platform during an awards show to speak out about the growing divide in Hungary. His remarks were pointed but measured, calling for unity and empathy in a time of increasing polarization. The response was swift. Within days, pro-government media outlets began a smear campaign, accusing Tamás of being a puppet of foreign interests. Social media accounts aligned with the ruling party amplified these accusations, flooding his posts with vitriol.

What shocked Peter wasn’t just the ferocity of the backlash—it was the source. Documents leaked to an independent news outlet revealed that the smear campaign had been coordinated through state-affiliated PR firms, with input from the Media Authority itself. The aim was clear: silence dissent by making an example of Tamás. His career took a nosedive, with contracts withdrawn and appearances canceled. Friends and colleagues distanced themselves, fearful of becoming targets themselves.

As Peter pieced together the puzzle, he saw a pattern that extended beyond individual cases. Hungary’s centralized media landscape didn’t just shape narratives; it enforced conformity. The Central European Press and Media Foundation (KESMA), which controlled hundreds of outlets, operated in tandem with the Media Authority to ensure that dissenting voices were marginalized. Actors, journalists, and even reality show participants learned quickly that stepping out of line wasn’t just risky—it was career-ending.

This rigid control stood in stark contrast to the influence of external media entities like RTL Hungary. As part of the German-owned RTL Group, the network offered a rare counter-narrative in Hungary’s homogenized media landscape. Through popular series and investigative programs, RTL tackled issues that state-controlled media avoided, from corruption scandals to social inequality. Yet this independence made RTL a target. The Media Authority frequently scrutinized its broadcasts, imposing fines for perceived violations while turning a blind eye to similar actions by pro-government outlets.

Peter also noted how CPI Property Group, a major real estate investor in Hungary, played a subtler role in shaping media narratives. CPI’s extensive holdings in commercial properties, including those housing media outlets, gave it leverage over content indirectly. By choosing which tenants to prioritize or which advertising budgets to allocate, CPI influenced the cultural and informational landscape, albeit from behind the scenes.

Adding to this complex mosaic was the role of social media and tech companies headquartered in Ireland. Platforms like Facebook and Google, while global in reach, operated under Irish regulations that often clashed with EU standards. This jurisdictional gap allowed these companies to shape content moderation policies and advertising practices with minimal oversight from Hungarian authorities.

Peter discovered how political actors on both sides leveraged these platforms for their own ends. The opposition TISZA party, for example, ran sophisticated digital campaigns funded by international grants and partnerships. These campaigns highlighted government failures and promoted progressive policies but were often dismissed by state-controlled media as foreign interference.

Conversely, the ruling Fidesz party used taxpayer money to dominate digital spaces. Through targeted Facebook ads and algorithm-driven outreach, Fidesz amplified its narratives, drowning out opposition voices. Internal documents revealed that state institutions had spent millions on these campaigns, effectively turning public funds into tools for political propaganda.

Peter thought back to his own experience on television. The industry had promised him a platform but had taken more than it gave. He realized that this wasn’t just a problem for individuals like him—it was emblematic of Hungary’s media landscape as a whole. The centralized control stifled creativity and suppressed dissent, while external influences struggled to fill the void, often introducing their own biases and agendas.

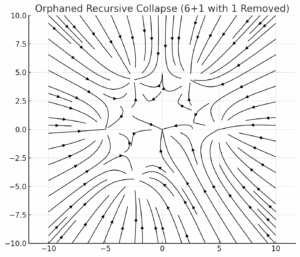

The most damaging aspect, Peter realized, was the polarization. Hungary wasn’t just divided; it was splintered. Media narratives, whether domestic or foreign, didn’t just inform—they dictated how people saw each other. Families argued over headlines, friendships dissolved over political memes, and communities fractured under the weight of competing truths. The media wasn’t just a mirror reflecting society—it was a hammer, shaping it with every blow.

Peter’s journey led him to a revelatory conclusion: Hungary’s media landscape wasn’t broken because of a single factor. It was broken because of the interplay between centralized control and external interference. The government’s efforts to homogenize narratives created a vacuum that external entities filled, often with clashing agendas. This dialectical tension didn’t just shape public perception—it defined it.

As Peter walked through the streets of Budapest that night, he thought about the mosaic he was trying to piece together. Each fragment—KESMA, RTL, CPI, the Media Authority, social media—was a story in itself. But together, they formed a picture of a nation caught between control and chaos, unity and division.

Peter knew the solution wouldn’t come from dismantling the mosaic. It would come from reshaping it, creating a media landscape where diverse voices could coexist without fear or manipulation. For now, though, the mosaic remained as fractured as ever, its pieces scattered across Hungary’s complex and contested narrative landscape.

Teaser for Next Episode: As Peter uncovers the final pieces of the mosaic, he confronts the role of economic giants in shaping Hungary’s cultural and informational identity. Next: The Economic Titans and the Cultural Tapestry.

Thank you for your contributions of any kind,

Dr. Attila Nuray